Deep Dive: CivicQA

CivicQA is an open-source constituent management platform.

CivicQA

Legislative-Assistants (LA’s) are staff members that work alongside members of government at all levels to help manage constituent inquiries, among other responsibilities. Our teams research found that many LA’s receive hundreds of emails per day, and are often equipped with nothing more than a Gmail or Outlook inbox to comb through them. CivicQA is a service aimed at assisting legislative-assistants in managing high volumes of mail from constituents. CivicQA began development at the start of 2021 as my team’s Informatics Capstone Project. The core functionality of CivicQA is a dashboard that helps LA’s visualize, categorize, and respond to inquiries with greater efficiency through embedded forms.

I worked alongside a designer, Lia, and two other engineers, Vivian and Amit. They were absolutely the best teammates I could have asked for, I could not recommend their skills more.

Depending on when you read this, CivicQA may still be deployed live although based on hosting costs it may not stay this way. Another great place to learn more is the Informatics Capstone Archive, you can also watch our demo video here. While a great many hours were taken to research, plan, and iterate on the design and features of CivicQA, this article will primarily cover the technical challenges involved with creating CivicQA’s backend.

Topics

Microservices

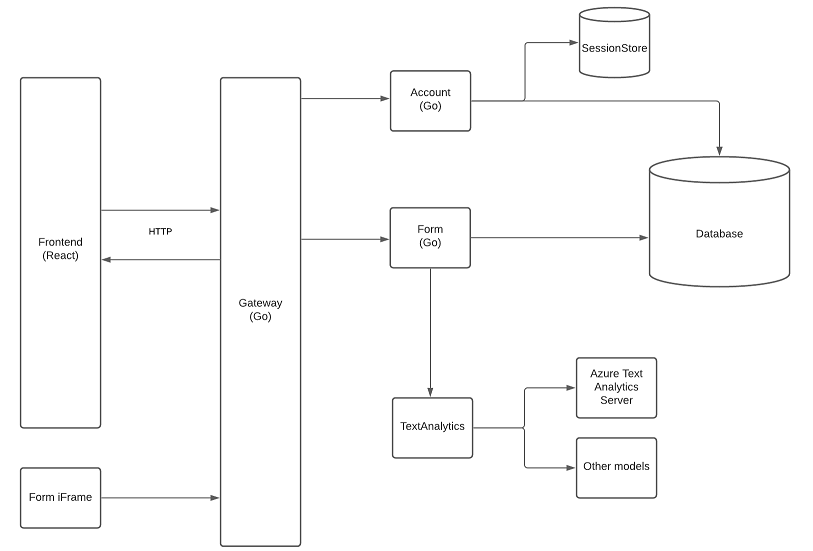

The backend of CivicQA is comprised of several independent, containerized, microservices. Here is a high level overview of the architecture.

Lets get straight to the point. Retrospectively, microservices were probably a mistake for CivicQA. To explain why this is, I have to give some context as to why we chose to write microservices in the first place. The other engineers on the team and I had all learned Go the previous year in our backend development course, INFO 441. INFO 441 was probably the most in-depth class I took through the iSchool at UW, we covered an absurd amount of content in just 10 weeks including Redis, AWS, Dev-Ops, Docker, Go, Node.js, and more. Given that we had all worked with Go before, it felt the the natural choice for CivicQA. We also decided to utilize the same architectural choices we had learned in the class, which primarily demonstrated a microservice based approach. To clarify, I still absolutely love microservice based architecture, however I have come to realize that like any tool, it has a specific time and place where it is useful, and CivicQA would have been simpler if we had just written a monolith.

The other sections below will provide more details about the challenges we faced outside of just the code because of this approach, but for now lets just look at the backend services themselves. Lets start with the first service written for CivicQA, one that isn’t even on the architecture diagram above.

Service: LogAggregator

LogAggregator is a service with 2 responsibilities, logging requests, and querying logs. As the name suggests, this service collected logs from all other services, storing them in a single place. In addition, a query endpoint existed to retrieve written logs for inspection, the final data-model for LogAggregator looked like this:

// Go

type LogEntry struct {

ID uint `gorm:"primarykey" json:"-"`

CorrelationID uuid.UUID `gorm:"column:correlationID;type:string" json:"correlationID"`

TimeUnix int64 `gorm:"column:timeUnix" json:"timeUnix"`

HTTPMethod string `gorm:"column:httpMethod" json:"httpMethod"`

RequestPath string `gorm:"column:requestPath" json:"requestPath"`

Service string `gorm:"column:service" json:"service"`

StatusCode int `gorm:"column:statusCode" json:"statusCode"`

Hostname string `gorm:"column:hostname" json:"hostname"`

Notes string `gorm:"column:notes" json:"notes"`

}

Nothing too surprising here, essentially just the who, what, when, and where for every request that came to the backend. Notably missing however, is the why. Given the privacy, cost, and time constraints of our project, it didn’t make sense to store more details about the contents and failure source about each request. Ultimately, 99% of debugging was just done by reading the docker logs of services directly, as they provided far more information about the cause of crashes and 5xx errors than LogAggregator could.

Despite its obsolescence, LogAggregator did serve as a great trial-run for future services, and helped us decide on patterns that would be pervasive throughout the rest of CivicQA. Several constructs originally written for LogAggregator eventually made their way into the Common module, we also used this services as an opportunity to create templates for Dockerfiles, Makefiles, documentation, and service boilerplate code that saved us lots of headache down the road.

Service: Form

Form contains the vast majority of CivicQA’s business logic, this service is responsible for creating and managing forms (essentially iFrame embedded surveys), recording responses, accessing text-analytics services, storing and managing response tags, as well as querying all of the above. If you think that sounds like a lot for a microservice then you’re right, given the scale of the project, Form wasn’t really micro anymore.

Just to give you an idea of how many features this single service supported, here is what the API routing setup looks like in main.go:

// go

/* snip */

// routers

router := mux.NewRouter()

api := router.PathPrefix(VersionBase).Subrouter()

// routes

api.HandleFunc("/forms", ctx.HandleGetForms).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/forms", ctx.HandleCreateForm).Methods("POST")

api.HandleFunc("/forms/{formID:[0-9]+}", ctx.HandleGetSpecificForm).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/responses", ctx.HandleGetResponses).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/responses/{responseID:[0-9]+}", ctx.HandlePatchResponse).Methods("PATCH")

api.HandleFunc("/responses/{responseID:[0-9]+}", ctx.HandleGetSpecificResponse).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/responses/{responseID:[0-9]+}/tags", ctx.HandleGetTags).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/responses/{responseID:[0-9]+}/tags", ctx.HandlePostTag).Methods("POST")

api.HandleFunc("/responses/{responseID:[0-9]+}/tags", ctx.HandleDeleteTag).Methods("DELETE")

api.HandleFunc("/form/{formID:[0-9]+}", ctx.HandleGetForm).Methods("GET")

api.HandleFunc("/form/{formID:[0-9]+}", ctx.HandlePostForm).Methods("POST")

api.HandleFunc("/tags", ctx.HandleGetAllTags).Methods("GET")

/* snip */

Note that this wasn’t originally our intention. The rapid development cycles of capstone demanded that we started work on the implementation before we had completely finished deciding on features, that meant as features were added, removed, and changed, it became more convenient to just add endpoints to Form instead of spinning them off into separate services. Retrospectively that should have been the sign to do the opposite perhaps, just roll the other services into Form.

Service: Common Functionality

As you might expect, as we developed these services, there were many instances where we needed the same functionality in 2 places. This lead us to create the Common module, essentially a library containing functions and structs that supported our development across many services. Beyond just upholding the DRY principle, Common enforced consistency throughout our codebase. One example of this is the definition of the User and SessionState structs within Common instead of the Account service. This meant a schema change to either of these was immediately reflected across all services where they are used, instead of having to update separate definitions in each one.

Another useful package within Common is Config. Config defines the Provider interface and implementations. This interface is used to provide configuration values across every single service in a consistent way. It also includes support for default/fallback values, as well as mocking for testing purposes.

// go (provider.go)

// Provider describes implementations of configuration providers

type Provider interface {

Name() string

SetVerbose(set bool)

GetOrFallback(key, fallback string) string

Get(key string) (string, KeyError)

verbose() bool

}

We use an implementation of this interface, EnvProvider to configure our services using environment variables in staging/test settings. Meanwhile MapProvider is used to configure unit-tests using map[string]string literals.

Database

In production, CivicQA uses a small MySQL database sever provided by DigitalOcean. This, however is not actually the start of the story for CivicQA’s data storage. All services that interact with CivicQA’s database do so through an ORM, specifically GORM. For those who don’t know, an ORM (Object–relational mapping) is a tool that allows you to write database queries in the native language of your backend, abstracting away whatever query language you are using.

Here is a sample from CivicQA’s account service’s GetByEmail function, which retrieves a user object given their email:

// Go

db.Where("email = ?", email).First(&user)

In raw SQL it might look something like this:

-- SQL

SELECT * FROM Users WHERE email = ? LIMIT 1;

That’s not bad, but when you add the boilerplate for preventing SQL injection, deserializing the result, and possibly writing separate implementations for different types of SQL, it gets pretty awful to manage. Especially in the middle of your Go codebase.

Another benefit to using an ORM, is that you can freely switch between different SQL databases depending on your needs, as long as your ORM supports them. For example, for local testing, CivicQA just uses SQLite, it’s fast, simple, easy to reset, and has zero start-up time. We also tested CivicQA using a MySQL database running in Docker before deploying with DigitalOcean’s managed MySQL. To GORM’s credit, this worked exactly as intended, beyond establishing a connection, the backend never needs to care about what database engine is being used. We write our queries with GORM, and it handles the rest behind the scenes while we focus on the business logic.

GORM did come with some challenges however, perhaps things have changed now, but when we wrote CivicQA, GORM had some pretty lacking documentation, especially around Joins and Relations. This left us with some pretty ugly queries in our final product, partially defeating the purpose of using an ORM. Here is an example from Form to update the active status of a response to a form in PatchByID:

// Go

var response model.FormResponse

result := g.db.

Model(&model.FormResponse{}).

Joins("JOIN forms ON forms.id = formResponses.formID").Where("forms.userID = ?", userID).

Where("formResponses.id = ?", responseID).

Take(&response, responseID)

result = g.db.Model(&response).Updates(map[string]interface{}{"active": state})

At this point, we’re basically just writing SQL with Go wrapped around it, and because of the limitations of GORM (partially Go’s fault too), we are forced to write what should be a single update as a query followed by an update. formResponse’s active field is a boolean, which defaults to false in Go; GORM would only update columns where the corresponding struct-field had a non-default value. The end result is this alternative syntax where we use a map[string]interface{} literal to explicitly mark that we want to update this field. While we caught this simpler case, imagine occasionally updating a numerical column to 0, or a string to the empty string based on user input, ideally your test cases would catch these updates silently failing, but depending on the complexity who knows…

Besides the use of GORM, CivicQA’s database is (fortunately) pretty uninteresting. The database follows a fairly standard relational model, and is comprised of the kind of tables you would expect for the domain: Users, Responses, Tags, and so on. One interesting note is the use of a single, shared database, instead of separate ones for each service. While this is not unheard of, it is sometimes considered an anti-pattern in microservice based architectures, and probably should have been another early warning that microservices were extraneous for this project.

DevOps

Simplicity was the name of the game when it came to DevOps for CivicQA. While I’m sure it would’ve been possible to set up huge Kubernetes and Terraform configurations to make CivicQA a hyper-scalable, ultra-redundant, distributed system, that was wayyyy beyond the scope of our capstone project. The minimum core infrastructure required to run CivicQA in production is literally a single VM and any SQL database. Our services all run on a Docker Swarm, which is great because we can reuse almost all of our docker-compose file from local development for production. I actually wrote up in-depth deployment documentation for CivicQA, but this just reflects the solution we landed on. The containerization of our services makes them very portable. Our core CI/CD works as follows:

- Somebody runs the build backend workflow

- This builds all backend containers, and pushes them to the registry

- Somebody runs the deploy workflow

- This SSHs into our swarm’s master node, pulls the containers from the registry, and deploys the stack on the swarm

Uhhh, yeah that’s it.

While GitHub Actions are pretty straightforward, developing workflows can be quite painful. As far as I am aware, there is still no officially supported way to test workflows locally (or even on a non-main branch) without just pushing to origin/main and hitting run. If you write code anything like me, this means you might end up with several “this should work now” commits before everything goes smoothly. This is where I want to give a huge shout-out to nektos/act, a command-line program that allows you to run workflows on your local machine via docker; act was a massive productivity boost when it came to working on deployment.

Keeping with the theme of simplicity, we landed on DigitalOcean as our cloud provider, it also helped that they were among the most affordable providers we looked at, given that we had a whopping $0 to work with. DigitalOcean is part of the GitHub Student Developer Pack, providing $100 of free credit. Their customer service team even went as far as to provide us additional credits to keep us running through our Capstone Demo Night when ours expired. DigitalOcean’s Load Balancers also saved us a ton of time getting CivicQA running over HTTPS, they offer fully managed certificates which meant I didn’t have to touch Let’s Encrypt or set up HTTPS on our services at all. We just set up SSL Termination for traffic headed to our API gateway, which can then safely use HTTP like it did locally to communicate with the rest of the backend isolated in the VPC.

Closing Thoughts

CivicQA was easily the most expansive project I worked on at the UW, over the approximately 6 months of work, I learned more than in any class I took about what it truly takes to create a production-ready product from the ground up. Design decisions always come with tradeoffs, and hindsight is 20/20; I’m sure that if we could start Capstone over again and rebuild CivicQA from the ground up using different architecture and tech, we’d find a whole new set of challenges, but that’s just the nature of software development. Each time we finish a project, we walk away a bit wiser, and with a couple new tools in our belt. Again I have to express how thankful I am to my teammates for their amazing work, there is absolutely no way I could have come remotely close to finishing something like this without them.