Deep Dive: brainfrick-rs

Brainfrick-rs is an optimizing compiler/interpreter written in Rust for Brainfuck, an esoteric programming language, known for its extreme simplicity.

Brainfuck Basics

For those who have never seen it before, here is a sample brainfuck program.

program.bf

++++++++[>++++[>++>+++>+++>+<<<<-]>+>+>->>+[<]<-]>>.>---.+++++++..+++.>>.<-.<.+++.------.--------.>>+.>++.

Wow, must do something cool right? Let’s run it with our fancy interpreter.

$ bfrs program.bf

Hello World!

oh.

A brainfuck program is made up of a series of instructions. There are exactly 8 instructions in standard brainfuck. All other characters are ignored and can be considered comments.

A brainfuck program works by manipulating a “tape” of memory cells by operation on a single cell at a time. This might sound awfully familiar if you’ve heard of a Turing Machine.

Here are all the brainfuck instructions and their equivalents in a more traditional language like C.

For the C versions, imagine that we’ve started by allocating a large char array and initializing char *ptr to point to the front of our array. This array will be our memory tape, and the pointer will point to the cell that we are operating on.

| Brainfuck | C | English |

|---|---|---|

> |

++ptr; |

Move the pointer right |

< |

--ptr; |

Move the pointer left |

+ |

++*ptr; |

Increment the cell at the pointer |

- |

--*ptr; |

Decrement the cell at the pointer |

. |

putchar(*ptr); |

Output the cell at the pointer |

, |

*ptr = getchar(); |

Set the cell at the pointer to a char from stdin |

[ |

while (*ptr) { |

Loop while the cell at the pointer is not 0 |

] |

} |

Jump back to the start of the loop if the current cell isn’t 0 |

If you’re going to try to write your own brainfuck compiler, this is a great place to start. Translate each brainfuck instruction into an instruction in your language of choice, and then execute it!

Here is our Hello World program transpiled to C using the table above.

helloworld.c

// Setup

char array[30000] = {0};

char *ptr = array;

//

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

while (*ptr) { // [

++ptr; // >

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

++*ptr; // +

while (*ptr) { // [

++ptr; // >

// ... Followed by another ~100 lines of beautiful C

Maybe don’t submit transpiled brainfuck for your first C assignment.

Right off the bat you can see that this isn’t the most expressive programming paradigm. Larger programs can take thousands, or even tens of thousands of instructions to do even the most basic tasks.

Brainfuck lacks a couple of the constructs that we take for granted in more… usable… programming languages. Most notably, we have no tool for abstraction. Brainfuck does not provide any means to define functions, meaning we have to write every painstaking instruction again, and again, and again. The only control-flow mechanism we have are while loops. We can also use these as an if statement, since if the cell at the pointer is already 0, we jump to the matching brace.

Implementing a brainfuck virtual machine

To write our brainfuck interpreter, we will “compile” our brainfuck source into equivalent instructions that we will then run on our own brainfuck Virtual Machine.

The snippets below are taken from brainfrick-rs but have been simplified or modified for this article.

First, we define our Instructions. Notice we only define 6 main instructions, we combined > with < and + with - since they are just negated versions of each other. Later on we will see the advantage to doing so.

src/instruction.rs

pub enum Instruction {

// Standard Brainfuck instructions

/// Commands: `>` | '<'

Shift(isize),

/// Commands: `+` | '-'

Alt(i16),

/// Command: `.`

Out,

/// Command: `,`

In,

/// Command: `[`

Loop,

/// Command: `]`

End,

// More instructions below!

// > Wait, I thought you said there were only 8?

// > Shhh... We'll get there!

We also implement TryFrom<char> on our Instruction type so we can easily parse from our program source.

src/instruction.rs

impl TryFrom<char> for Instruction {

type Error = ();

/// Convert value into an `Instruction`.

/// Returns `Err(())` if value is not a valid `Instruction`.

fn try_from(value: char) -> Result<Self, Self::Error> {

use Instruction::*;

// Convert each source token into it's corresponding

// Instruction, or Err(()) if it is not a valid brainfuck instruction

Ok(match value {

'>' => Shift(1),

'<' => Shift(-1),

'+' => Alt(1),

'-' => Alt(-1),

'.' => Out,

',' => In,

'[' => Loop,

']' => End,

_ => return Err(()),

})

}

}

We return an Err for any invalid characters, we then ignore then when parsing the program.

Here’s how we actually perform the parsing to get a collection of instructions for our VM.

Additionally, we will take this opportunity to implement our first optimization; we will match loop instructions to their corresponding ends ahead of time. The approach here might look familiar if you’ve done a lot of leetcode.

src/compiler.rs

pub fn compile(src: &str) -> Program {

// parse source into instructions

let mut instructions = src

.chars()

.map(Instruction::try_from)

.filter_map(Result::ok) // keep only valid instructions

.collect::<Vec<_>>();

// match opening and closing Loop instructions ('[' and ']').

// we could use a map here as well, but we opt for a vector for increased performance at the cost of using a flat `usize` memory per instruction

let mut loop_map = vec![0; instructions.len()];

let mut stack = Vec::new();

for (ptr, ins) in instructions.iter().enumerate() {

match *ins {

Instruction::Loop => stack.push(ptr),

Instruction::End => {

let open = stack.pop().unwrap();

loop_map[open] = ptr; // map '[' -> ']'

loop_map[ptr] = open; // and ']' -> '['

}

_ => {}

}

}

// Return the final compiled Program

Program {

instructions,

loop_map,

},

}

Let’s run our Hello World program through what we have so far and see what comes out!

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Loop,

Shift(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Loop,

Shift(1),

...

Nice, the correspondence to our C code is clear.

Now we can create a VM to execute the instructions. Much like the C version, we have some setup to do before we can start running our code.

Let’s define a struct to act as our VM.

src/vm.rs

/// Default memory size for VM.

const MEM: usize = 30_000;

/// Brainfuck VM.

pub struct VM {

/// Compiled Brainfuck program

program: Program,

/// Program Memory

data: Box<[u8; MEM]>,

/// Memory pointer

ptr: usize,

}

Now we define a run function to execute our brainfuck code. First, we will set up some infrastructure to loop through our instructions, stopping once we reach the end.

src/vm.rs

impl VM {

/// Runs the VM

pub fn run(mut self) {

// index of the current instruction. Kind of like a 'line number'.

let mut instruction_ptr = 0;

// we stop once we pass the last instruction

while instruction_ptr < self.program.instructions.len() {

// current instruction to execute

let instruction = &self.program.instructions[instruction_ptr];

match instruction {

///////////////////////////////////////

// todo: implement the instructions! //

///////////////////////////////////////

};

// move to the next instruction

instruction_ptr += 1;

}

}

}

Now, we just run the appropriate behavior based on our current instruction.

src/vm.rs

impl VM {

/// Runs the VM

pub fn run(mut self) {

// index of the current instruction. Kind of like a 'line number'.

let mut instruction_ptr = 0;

// we stop once we pass the last instruction

while instruction_ptr < self.program.instructions.len() {

// current instruction to execute

let instruction = &self.program.instructions[instruction_ptr];

match instruction {

Shift(count) => {

self.ptr = (self.ptr as isize + count) as usize;

},

Alt(amount) => {

self.data[self.ptr] = match *amount >= 0 {

true => self.data[self.ptr].wrapping_add(*amount as u8),

false => self.data[self.ptr].wrapping_sub(-amount as u8),

};

}

Out => {

print!("{}", self.data[self.ptr] as char);

},

In => {

self.data[self.ptr] = std::io::stdin()

.bytes().next().unwrap().unwrap();

},

Loop => {

if self.data[self.ptr] == 0u8 {

// jump to end of loop if cell is 0

instruction_ptr = self.program.loop_map[instruction_ptr];

}

}

End => {

if self.data[self.ptr] != 0u8 {

// jump back to start of loop if cell is not 0

instruction_ptr = self.program.loop_map[instruction_ptr];

}

}

};

// move to the next instruction

instruction_ptr += 1;

}

}

}

It’s a lot to take in at once but it’s very simple.

Our loop will run until our instruction_ptr reaches the end of our program. In each iteration, we grab the Instruction at instruction_ptr, and use match to find the implementation. Each implementation is similar to the C version, but contains some extra logic to handle wrapping semantics and the use of types with different Signednesss.

If you have a keen eye you’ll notice some weird choices right away. For example, why bother making > and < into the same Shift(isize) instruction if we have to branch to handle it anyway… and why include an isize field at all if each > and < will only move us 1 cell? Wouldn’t it be simpler to have separate instructions and only increment or decrement by 1 without handling mixed sized and un-sized types?

This brings us to our next (and in my opinion, most interesting) chapter.

Optimizing Brainfuck

Before we start, I want to give a huge shout-out to the references I used while working on this project. They can all be found at the bottom of this article. For some brainfuck sample programs and their authors, please check the samples/ directory of the repository.

As we discussed before, brainfuck doesn’t have any mechanism for defining functions, which means we have to repeat ourselves endlessly while writing programs. The crux of brainfuck optimization is finding common or inefficient patterns and replacing them with something faster.

Contracting Repeated Instructions

Lets take a very simple piece of brainfuck

>>+++<<

This moves the pointer 2 right, increments the current cell by 3, and moves the pointer back. Let’s translate this chunk into C and our VM Instruction’s and see if we can find any way to make it better.

chunk.c

++ptr;

++ptr;

++*ptr;

++*ptr;

++*ptr;

--ptr;

--ptr;

Instructions

Shift(1),

Shift(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Alt(1),

Shift(-1),

Shift(-1),

Brainfuck only lets us alter/shift by one at a time, but at runtime, there’s no reason for us to pay this cost. We can ‘contract’ repeated instructions into a single instruction with an O(1) cost.

This applies to repeated >/< and +/- instructions. This is why we defined them together in our Instruction enum, so that we can easily fuse them together.

src/compiler.rs

fn contraction_optimizer(mut instructions: Vec<Instruction>) -> Vec<Instruction> {

let mut output = Vec::new();

let mut input = instructions.drain(..).peekable();

let mut next: Option<Instruction> = input.next();

// loop over our input instructions

while let Some(cur) = next {

match cur {

// ex: ">><>>" -> Shift(3)

Instruction::Shift(mut count) => {

// keep contracting while the next instruction is a Shift

while let Some(Instruction::Shift(more)) = input.peek() {

count += *more;

input.next();

}

// output our final contracted Shift

output.push(Instruction::Shift(count));

}

// ex: "+--+-" -> Alt(-1)

Instruction::Alt(mut count) => {

// keep contracting while the next instruction is an Alt

while let Some(Instruction::Alt(more)) = input.peek() {

count += *more;

input.next();

}

// output our final contracted Alt

output.push(Instruction::Alt(count));

}

// other instructions are kept unchanged

other => output.push(other),

}

next = input.next();

}

output

}

We can stick a call to this optimization function right in our compile function between our parsing and loop matching. We always want to do loop matching last in case one of our optimizations moves (or removes) braces.

After introducing this optimization, lets look at how our C and Instructions have changed.

chunk_contracted.c

ptr += 2

*ptr += 3;

ptr -= 2;

Instructions Contracted

Shift(2),

Alt(3),

Shift(-2),

Nice! Now our VM has several less instructions to execute.

We can run some benchmarks against popular brainfuck programs to see how our runtime has changed. fib11.bf is a brainfuck program to compute and output the first 11 numbers in the Fibonacci sequence.

The output looks like this:

$ bfrs fib11.bf

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89

Unoptimized:

$ cargo bench

...

Fib 11 time: [228.53 µs 230.09 µs 231.95 µs]

Contraction Optimized:

$ cargo bench

...

Fib 11 time: [168.61 µs 169.50 µs 170.51 µs]

change: [-27.754% -26.550% -25.161%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has improved.

Not bad!

Removing No-Ops

Our contraction optimization has introduced an interesting possibility, it’s now possible for us to encounter ‘no-op’ instructions that don’t do anything. While these instructions take up very little memory and time, we can still choose to eliminate them to speed up our program. While this might make a difference in very tight loops, in a well written brainfuck program, these are very unlikely because they can often be spotted and simplified while writing the program.

Here are some examples:

>< generates Shift(1), Shift(-1) which contracts to Shift(0).

+- generates Alt(1), Alt(-1) which contracts to Alt(0).

This applies for all balanced consecutive groups as well like >><<>< or +--+.

We can add an additional optimizer function to call after our contraction optimizer that eliminates these ‘no-ops’ from our program.

src/compiler.rs

fn no_op_optimizer(instructions: Vec<Instruction>) -> Vec<Instruction> {

use Instruction::*;

let mut output = vec![];

for instruction in instructions {

// if our instruction isn't Alt(0) or Shift(0), keep it

if !matches!(instruction, Alt(0) | Shift(0)) {

output.push(instruction);

}

}

output

}

Clear Loop Optimization

Another very common construct in Brainfuck is the ‘clear loop’. In fact, this appears 9 times in our fib11.bf program.

It looks like this: [-].

Let’s transpile it to try to make more sense of it:

clear.c

while (*ptr) {

--*ptr;

}

Hmm, so this chunk decrements the current cell in a loop. This will always run until the cell reaches 0. Couldn’t we just set the value of the cell to 0 in one step? Exactly!

For this, we will introduce a new Instruction, Clear, to replace this O(n) operation with an O(1) one.

Here is our optimization function:

src/compiler.rs

fn clear_loop_optimizer(instructions: Vec<Instruction>) -> Vec<Instruction> {

use Instruction::*;

let mut output: Vec<Instruction> = Vec::new();

for instruction in instructions {

output.push(instruction);

if output.len() >= 3 {

// ex: "[-]" -> Clear

if let [Loop, Alt(-1), End] = output[output.len() - 3..] {

// if we find the sequence, replace it with 'Clear'

remove_n(&mut output, 3);

output.push(Clear);

};

}

}

output

}

If we ever encounter the Instruction sequence Loop, Alt(-1), End, we just remove those 3 instructions, and substitute a single Clear.

Now in our VM’s run function, we add a branch to support our new instruction

src/vm.rs

Clear => {

self.data[self.ptr] = 0;

}

Since each cell is represented by a single byte (u8), this optimization could save us up to 255 decrements each time we use it.

Let’s run our benchmark again and see what’s changed

Unoptimized:

$ cargo bench

...

Fib 11 time: [398.57 µs 416.14 µs 438.76 µs]

Contraction, No-Op, and Clear Optimized

$ cargo bench

...

Fib 11 time: [176.08 µs 178.05 µs 180.35 µs]

change: [-65.772% -63.588% -61.228%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has improved.

🤯

There are plenty of other optimization you can make, my compiler implements one more that replaces certain copy/multiply operations with some new instructions, but it’s not quite as simple as the others. I’ll leave some brainfuck below and you can think about how you might try to optimize them by introducing new instructions. (Hint: try transpiling them to a language you like after applying our previous optimizations, this should give you a hint as to what’s happening here)

[->+<]

…

[->>>++<<<]

…

[->>+<<]

Check out copy_loop_optimizer in src/compiler.rs for the answer.

Pushing it to the limit

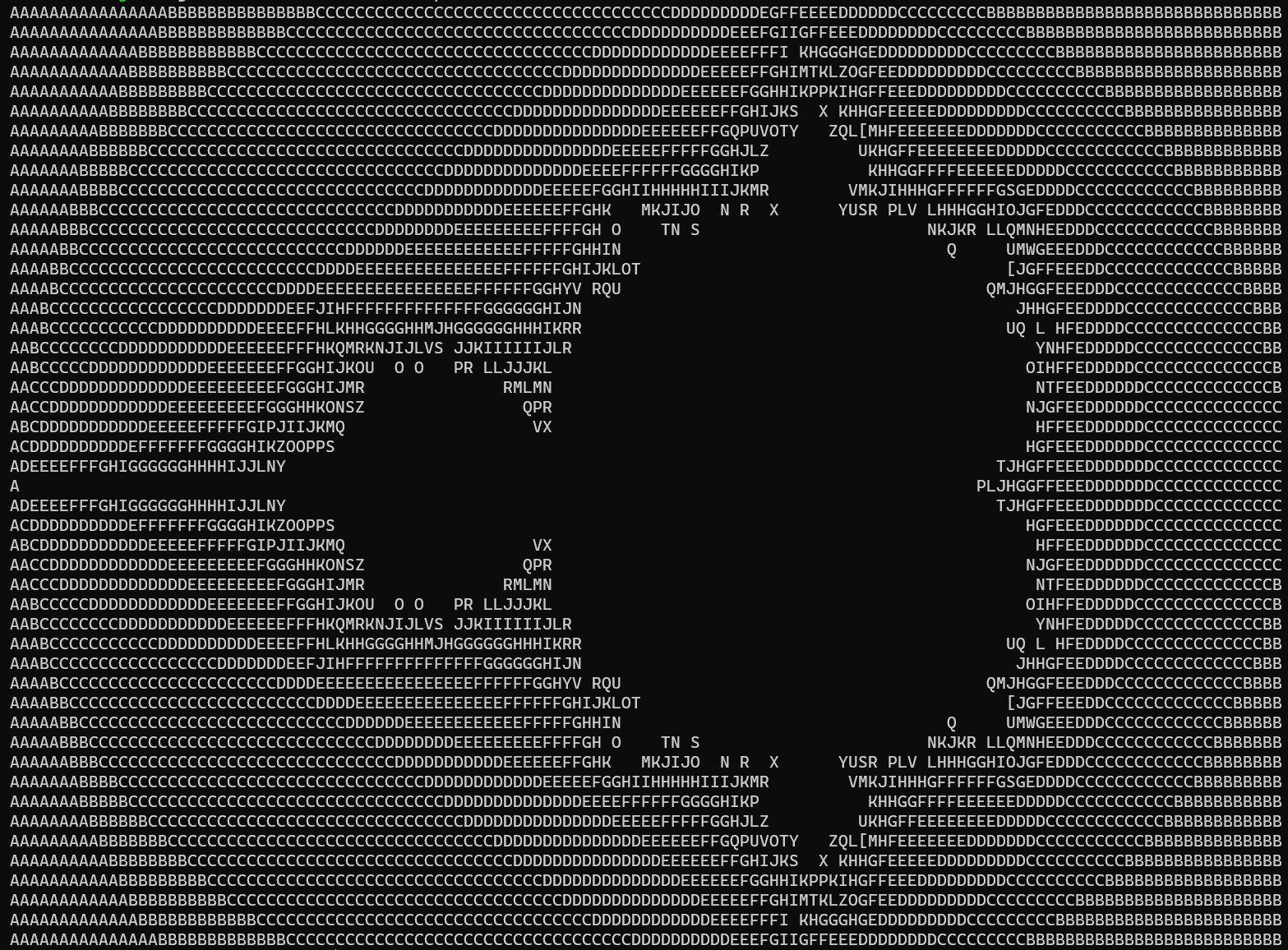

mandelbrot.bf is a 11,900 instruction brainfuck program to render an ASCII Mandelbrot fractal.

The output looks something like this.

Let’s try timing the runtime with and without optimizations to see the impact. Unfortunately it isn’t quite fast enough to make use of our rust benchmark framework, Criterion, so we’ll just use our shell utility time instead.

Unoptimized:

$ time cargo run --release -- samples/mandelbrot.bf

...

real 0m18.641s

user 0m0.000s

sys 0m0.015s

Fully Optimized:

$ time cargo run --release -- samples/mandelbrot.bf

...

real 0m5.276s

user 0m0.000s

sys 0m0.015s

I’m sure these times would be really impressive to a computer scientist in the 60’s, but knowing what it took to get here makes it impressive to me as well 😊