Demo: ants, ants, ANTS!

Camera Controls (click game frame)

Q/E - zoom in/out

W/A/S/D - pan

Ants (again)

ants-again is an ant pheromone simulation written in Go and compiled for WASM using ebitengine.

The ‘again’ part of the name comes from the fact that this is not my first time attempting to simulate ants in this manner, but it’s the first that I’m happy enough with to share.

What am I looking at?

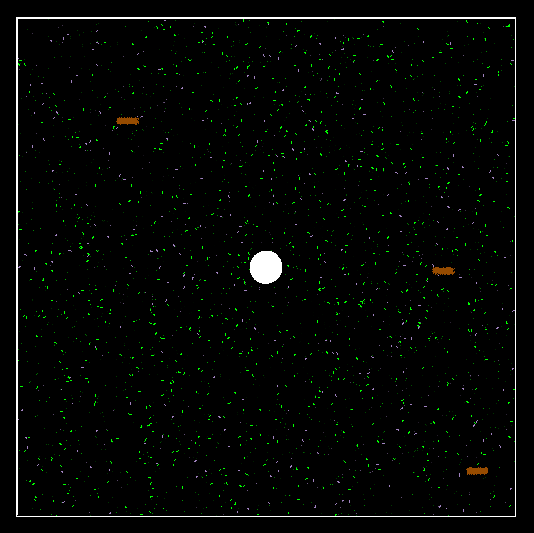

Each colored speck moving around the screen represents an ant.

- Green ants are ‘foraging’ ants searching for food

- Lilac ants are ‘returning’ ants holding food and looking for the hill

The large white circle in the center represents the hill. And the brown bricks scattered about represent food sources.

Pheromones

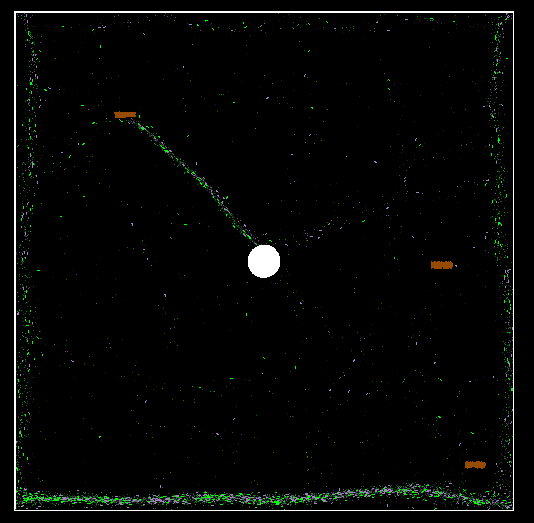

If you zoom in a bit (click the game frame, hold Q), you will also notice small fading points left behind by ants of the same color.

These points represent ‘pheromones’ that are left behind by ants, and fade in strength over time, eventually disappearing.

Pheromones are the only thing these simulated ants can sense; they are otherwise ‘blind’ to the world around them. They cannot sense food or the hill directly, and can only interact with them by bumping into them by chance.

ants and some pheromones

Discovering paths

Ants have one of two states. They remain in their current state until they accomplish their objective. Foraging ants (green) will become returning ants (lilac) when they encounter food. Returning ants will become foraging ants when they encounter the hill.

Ants drop and sense pheromone according to their state:

- Foragers will drop foraging pheromone and sense returning pheromone

- Returners will drop returning pheromone and sense foraging pheromone

This allows ants to work together to discover paths between the hill and food. When a forager finds food, it becomes a returner. The new returner senses pheromone left by other foragers to find its way back to the hill. As it returns to the hill, it leaves behind returning pheromone that the remaining foragers can follow to find the same food it found. As more and more ants discover the same path, the pheromones they leave behind reinforce the path. Since pheromones fade over time, shorter and busier paths get reinforced, while paths left behind by lost ants fade away.

Improving ant behavior

Getting the ants to converge on good paths quickly is a product of several tricks and optimizations. Many of these are inspired by real-world ant behavior.

Pheromone weighting

When an ant senses pheromone, they only consider those in a fairly small area around them. This prevents them from getting distracted by far-away pheromones left by ants collecting other food sources.

In addition, ants are more strongly influenced by nearby pheromones, as well as pheromones that point in a direction more similar to their current heading.

Pheromone gradient

These are fairly important behaviors because of the ‘pheromone gradient’. As a trail left by an ant starts to decay, the gradient points towards the ant. Pheromones left more recently are stronger, those left several seconds ago are almost gone. Another ant following this trail would then be more likely to follow the gradient, but this is not quite the effect that we want. If a forager follows directly behind a returner, they are likely walking towards the hill, not the food source the returner found. The same applies in reverse.

By applying more weight to closer, and more directionally similar pheromones, we make it more likely that an ant follows the trail in the direction we want.

Pheromone inventory

To help ants forget bad paths, each ant has a limited ‘inventory’ of pheromone that they can drop. Once an ant has exhausted their inventory, they can’t drop any more pheromone until they accomplish their goal.

Pathological outcomes

Finding a good balance between pheromone influence, decay, drop rate, and other parameters is challenging. If poorly selected, several pathological outcomes are possible.

Non-convergence

If ants are not sensitive enough to pheromones, if pheromones decay too fast, or if ants have a mis-sized sensing radius, it’s possible that they fail to effectively converge on a path. In this case, ants continue to wander aimlessly, only sometimes collecting food by random chance.

Over-convergence

The opposite scenario is also possible. If ants are over-influenced by pheromone, they will follow paths too strictly, and fail to discover more optimal paths. An even worse failure mode exists where foraging and returning ants create a circular path that does not pass near food or the hill. In that scenario, they may follow each other in an endless loop and never accomplish their goal. This is largely mitigated by having a reasonably small pheromone inventory, but it is still possible that they discover a very long and inefficient path that eventually does result in food collection.

Implementing and optimizing

ebitengine is an extremely minimal game engine. It exposes a simple interface to run and render games that may look familiar if you’ve done some game development before. An ebitengine game implements an interface that includes the methods Update() and Draw(). During Update, the game is expected to advance the simulation forward one step. This method is called by the engine every 1/60th of a second. Likewise, during Draw, the game is expected to render itself to the screen. This is also called every 1/60th of a second.

By separating Update and Draw, we can implement game-logic and rendering separately.

Rendering

I’ll touch on this first because it’s simpler. My Draw function is implemented as a set of loops that iterate over and draw elements of my game to the screen.

For example, drawAnts:

func (g *Game) drawAnts() {

for _, ant := range g.ants {

// `tail` point 5 units opposite the direction the ant is facing (`ant.dir`)

tail := ant.Add(ant.dir.Normalize().Mul(-5))

// decide what color the ant should be based on ant.state

c := GREEN

if ant.state == RETURN {

c = LILAC

}

// draw a line from ant position to tail.

vector.StrokeLine(

g.world, // "world-space"

float32(ant.X), float32(ant.Y), // from

float32(tail.X), float32(tail.Y), // to

2, c, false) // thickness, color, anti-aliasing

}

}

Food sources and the hill are drawn in a similar manner. Pheromones are a bit different. Because the number of pheromones in the simulation can reach tens-of-thousands depending on parameters, drawing them is performance intensive.

The vector drawing package provided by ebitengine is sufficient for most things, but it requires an engine draw call every time it’s used. For pheromones we instead maintain a buffer representing every game pixel and render them all at once with a single call.

Using this API, each pixel in the game is represented by 4 bytes, one for each color channel (RGBA). If our game world is 1000x1000 pixels, this means our buffer needs to be 1000*1000*4 bytes, or 4MB. Not too bad.

Full disclosure, this was originally implemented with the help of ChatGPT.

func (g *Game) drawPheromones() {

// Clear buffer to black (or background color)

for i := range g.px {

g.px[i] = 0

}

writePheromones := func(ph spatial.Spatial[*Pheromone], color color.RGBA) {

for pher := range ph.PointsIter() {

// Fade color by pheromone amount (0..1)

c := Fade(color, pher.amount)

x := int(pher.X)

y := int(pher.Y)

// don't bother rendering anything outside the bounds of the game

if x < 0 || x >= GAME_SIZE || y < 0 || y >= GAME_SIZE {

continue

}

idx := 4 * (y*GAME_SIZE + x)

g.px[idx+0] = c.R

g.px[idx+1] = c.G

g.px[idx+2] = c.B

g.px[idx+3] = 255 // alpha channel

}

}

writePheromones(g.foragingPheromone, DARK_GREEN)

writePheromones(g.returningPheromone, DARK_LILAC)

// Write the pixel buffer to the ebiten.Image once

g.world.WritePixels(g.px)

}

I also left an unused naiveDrawPheromones function in the source code that is implemented like our other draw functions. It does work well enough for smaller simulation sizes.

Camera

I achieved the camera zoom/panning behavior by representing the game as a sub-image. When you adjust the camera, we update the transform applied to the game sub-image before drawing it to the screen. That also makes it easy to draw game elements in “world-space” without worrying about the “screen-space” size changing if I update the resolution or window size of the game.

That’s… pretty much it for rendering.

Simulation

The Update function takes a similar approach to Draw. Each element of the game has a loop in it that iterates over game elements and advances their state by a step.

Ants

func (g *Game) updateAnts() {

for _, ant := range g.ants {

// move the ant forward

ant.Vector = ant.Add(ant.dir.Normalize().Mul(float64(g.params.AntSpeed)))

// prevent the ant from escaping the boundary of the game

keepInbounds(ant)

if util.Chance(g.params.PheromoneSenseProb) {

// ... smell nearby pheromones, update ant.dir ...

}

if ant.state == FORAGE {

// ... do foraging ant stuff, change to returning ant if we bump food ...

}

if ant.state == RETURN {

// ... do returning ant stuff, change to foraging ant if we bump hill ...

}

if ant.pheromoneStored > 0 && util.Chance(g.params.PheromoneDropProb) {

// ... drop some pheromone on the ground

}

// randomly turn a few degrees

ant.dir = ant.dir.Rotate(util.Rand(-g.params.AntRotation, g.params.AntRotation))

}

}

Other elements

Food, pheromone, and hills are less interesting. If food is exhausted, we remove it from the sim. Pheromone decays a bit each tick, we remove it when it reaches 0. The hill doesn’t even have an update function, it just sits there.

Spatial hashing

Lots of our game logic relies on us being able to find elements ‘nearby’. With a more heavy-weight game engine, there might be a built-in way to do this, but here we’re on our own. Remember that each tick, an ant needs to sense nearby pheromone and compute the impact on direction. If we have 1000 ants, and 10,000 pheromones, computing that the naive way would require a nested loop with 10,000,000 iterations every tick. That is not feasible if our target is running ~60 ticks per second.

Instead, anything that we need to search an area for is stored in a data structure called a spatial hash. In ants-again, pheromone, food sources, and the hill are all stored in spatial hashes. This data structure allows us to quickly find elements in a given area, without checking every single element.

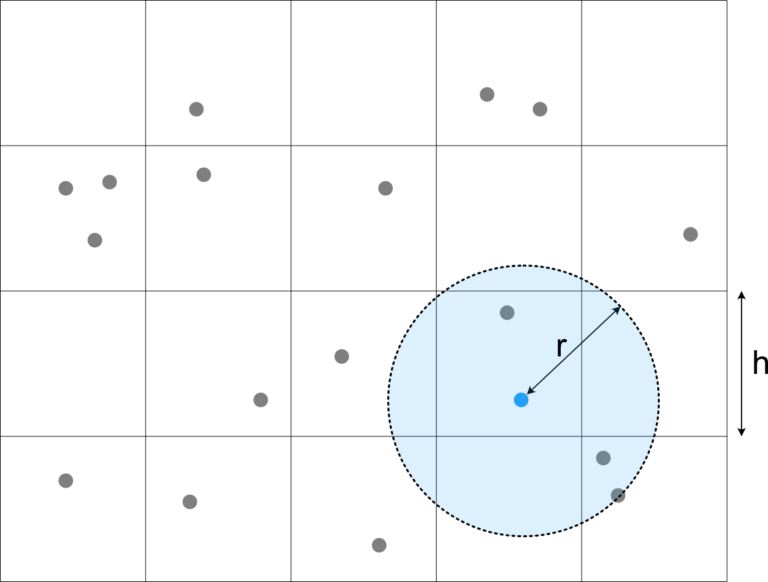

A spatial hash works by storing elements in a set of ‘cells’. The ‘cell’ that an element belongs to is determined by a hash of its position (x,y coordinates) after dividing by ‘cell size’ and rounding down. If we want to find elements in the spatial hash within a given radius of a point, we only need to search cells that overlap with the circle formed by our point and radius. When we consider a given point, we discard it if the distance is outside of our circle.

source: leetless

source: leetless

When deciding the cell size, there is a performance tradeoff. Choose too large, and you will have to iterate many elements that end up being discarded. Too small, and you have to search many cells. Generally, your cell size should be similar to the size of the queries you expect to be making.

Other spatial data structures

Spatial hashes are just one of many spatial data structures. Each one provides tradeoffs on the performance of inserting, querying, and updating. Early iterations of this project used a KD-Tree instead of a spatial hash, but it proved to be less performant and more complex. The spatial package provides the interface used within the game for interacting with spatial data structures. This makes it possible to experiment with alternative implementations.

type Spatial[T vector.Point] interface {

Insert(p T)

PointsIter() iter.Seq[T]

Remove(p T) T

RadialSearchIter(center vector.Point, radius float64) iter.Seq[T]

Len() int

}

Profiling

The Go standard-library has a package called "runtime/pprof" that makes it easy to collect pprof profiles to analyze CPU, memory, and traces. go tool pprof can create graphviz files with the -dot flag. I used this pretty extensively to identify CPU hot-spots. Unsurprisingly, garbage collection, and querying our spatial hashes are still by far the most time-consuming parts of our program.

Here is the output from ~30 seconds of simulation. (click to open visualizer)

Parameter optimization

As mentioned above, there are many tradeoffs to be made that result in vastly different ant behavior. There are many variations that produce stable simulations with different characteristics. It’s possible to create very fast ants that find and forget paths quickly, or slow and steady ants that take a while to converge, but keep finding their way back to a food source until it is exhausted.

I spent a little bit of time trying to automate this fiddling with a rudimentary form of parameter optimization.

Game parameters were factored into a single struct

type Params struct {

AntSpeed float64

AntRotation float64

AntPheromoneStart int

PheromoneSenseRadius float64

PheromoneSenseCosineSimilarity float64

PheromoneDecay float32

PheromoneDropProb float64

PheromoneInfluence float64

PheromoneSenseProb float64

}

Then, we pick random values (within bounds) for each parameter, and run the game for a fixed number of ticks (180 * 60, 3 ‘simulation’ minutes). For this, we can just run Update in a loop as fast as possible, and skip rendering entirely.

Afterwards, we evaluate the performance of the random parameters based on how much food the ants collected. If we beat our previous best score, we output the params. We can run multiple samples for each set of parameters, and test multiple parameters in parallel. Go makes this pretty easy, especially with a little bit of ChatGPT help.

This is essentially a random search of the parameter space. It was useful to find interesting parameter presets, but didn’t produce anything too groundbreaking.

An interesting future project might be applying a more sophisticated “machine-learning” approach here by using something like gradient descent, or ironically enough, ant-colony optimization.

Lessons, challenges, closing thoughts

As I mentioned at the start, this wasn’t my first time trying to simulate ants and pheromones. There are a ton of tradeoffs and alternative strategies to choose, and that makes it difficult to find and tune an approach enough to get a stable simulation. A few of those choices include:

- discrete pheromones vs. diffusing pheromone field

- pheromones as points vs. vectors

- spatial data structures

- continuous vs. discrete position representations

- random movement vs. pheromone influence

In the future, I think it would be neat to include some sliders and dropdowns to alter parameters and behavior of a running simulation.

Those who know me would probably say I’m at least skeptical of AI tools, but ChatGPT was a pretty invaluable source for brainstorming solutions to problems I encountered along the way, and optimizing inefficient code. Other than that, a huge thank you to the implementors of similar projects whose games and code I looked at extensively while creating this project. I’ve tried to include links to all of them below.